A surefire [sic] way to get to look for another job in IT is to lose important data. Typically if a user in any organisation stores data he or she expects that data to be safe and always retrievable (and as we all know data loss in storage systems is unavoidable). Data also keeps growing, a corollary to Parkinson’s law is that data expands to fill the space available for storage, just like clutter around your house.

Because of the constant growth of data there is a greater need to both protect said data but also to simultaneously store it in a more space efficient way. If you look at large web-scale companies like Google, Facebook, and Amazon they need to store and protect incredible amounts of data, they do however not rely on traditional data protection schemes like RAID because it is simply not a good match with the hard disk capacity increases of late.

Sure sure, but I’m not Google…

Fair point, but take a look at the way modern data architectures are built and applied even in the enterprise space, looking at most hyper-converged infrastructure players for example they typically employ a storage replication scheme to protect data that resides on their platforms, for them they simply cannot not afford the long rebuild times associated with multi-Terabyte hard disks in a RAID based scheme. Same goes for most object storage vendors. As as example let’s take a 1TB disk, it’s typical sequential write sits around 115 MBps, so 1.000.000 MB / 115 MBps = approximately 8700 seconds which is nearly two and a half hours. If you are using 4TB disks then your rebuild time will be at least ten hours. In this case I am even ignoring the RAID calculation that needs to happen simultaneously and the other IO in the system that the storage controllers need to deal with.

RAID 5 protection example.

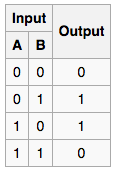

Let’s say we have 3 HDDs in a RAID 5 configuration, data is spread over 2 drives and the 3rd one is used to store the parity information. This is basically a exclusive or (XOR) function;

Let’s say I have 2 bits of data that I write to the system, disk 1 has the first bit, disk 2 the second bit, and disk 3 holds the parity bit (the XOR calculation). Now I can lose any of the 2 bits (disks) and the system is able to reconstruct the missing bit as demonstrated by the XOR truth table below;

Let’s say I write bit 1 and bit 0 to the system, 1 is stored on disk A and 0 is stored on disk B, if I lose disk A [1], I still have disk B [0] and the parity disk [1]. According to the table B [0] + parity [1] = 1 thus I can still reconstruct my data.

But as we have established that rebuilding these large disks is unfeasible, what the HCI builders do is replicate all data, typically 3 times, in their architecture as to protect against multiple component failures, this is of course great from an availability point of view but not so much from a usable capacity point of view.

Enter erasure coding.

So from a high level what happens with erasure coding is that when data is written to the system, instead of using RAID or simply replicating it multiple times to different parts of the environment, the system applies slightly more complex mathematical functions (including matrix, and Galois-Field arithmetic*) compared to the simple XOR we saw in RAID (strictly speaking RAID is also an implementation of erasure coding).

There are multiple ways to implement erasure coding of which Reed-Solomon seems to be the most widely adopted one right now, for example Microsoft Azure and Facebook’s cold-storage are said to have implemented it.

Since the calculation of the erasure code is more complex the often quoted drawback is that it is more CPU intensive than RAID. Luckily we have Intel who are not only churning out more capable and efficient CPUs but are also contributing tools, like the Intelligent Storage Acceleration Library (Intel ISA-L) to make implementations more feasible.

Erasure Coding 4,2 example.

Erasure codes are typically quite flexible in the way you can implement them, meaning that you can specify (typically as the implementor, not the end-user, but in some cases both) the number of data blocks to parity blocks. This then impacts the protection level and drive/node requirement. For example if you choose to implement a 4,2 scheme, meaning that each file will be split into 4 data chunks and for those 4 chunks 2 parity chunks are calculated, this means that in a 4,2 setup you require 6 drives/nodes.

The logic behind it can seem quite complex, I have linked to a nice video explanation by Backblaze below;

!BackBlaze EC(http://img.youtube.com/vi/jgO09opx56o/0.jpg

- (http://web.eecs.utk.edu/~plank/plank/papers/CS-96-332.pdf)